Alexander Calder

Born August 22, 1898 in Lawnton, Pennsylvania, Alexander Calder already had art in his blood—his mother Nanette was a painter, and his father Alexander was a sculptor. As a young boy, Calder was already fascinated with mechanics and sculpting, making his own toys and small brass animal sculptures. Continuing his kinetic interests, he graduated in 1919 from Stevens Institute of Technology with a degree in mechanical engineering, though after a few years of working at various engineering jobs, Calder decided to pursue a career as a painter, and enrolled at the Art Students League of New York from 1923-1926. During this time he worked as a freelance artist, sketching the beloved Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey circuses and drawing scenes of the New York street life and attractions. Read More

Attracted by its rich artistic reputation, Calder moved to Paris in 1926 to attend the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. That same year, he exhibited at the 1926 Salon des Indépendants, and by 1927 he had debuted Cirque Calder, a miniature circus sculpture made of wire and began giving performances. Once Calder had discovered the possibility of using line in a sculptural third dimension with the use of wire, he never turned back, coining the term “linear sculptures” and revolutionizing the way the art world understood three-dimensional art.

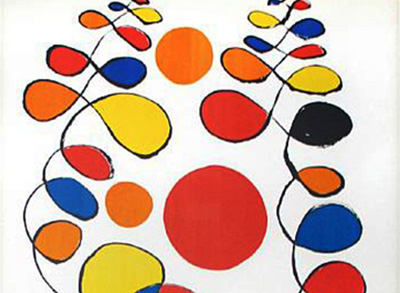

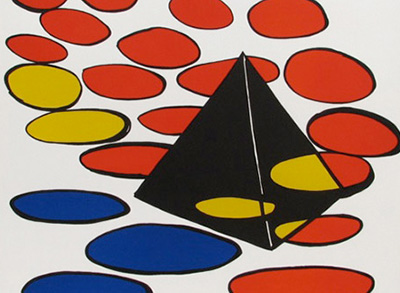

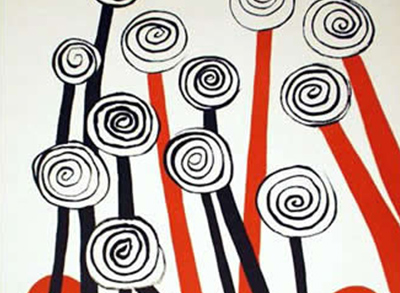

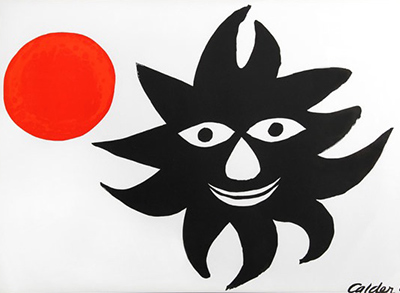

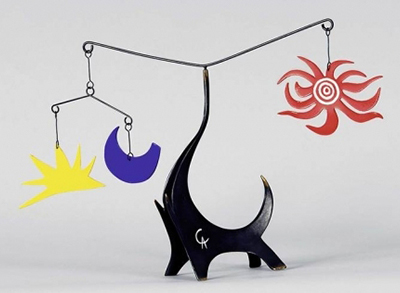

But it was a visit to Dutch artist Piet Mondrian’s studio in 1930 that spurred Calder to make a distinguishing leap into abstraction. Upon viewing large rectangles of painted cardboard tacked all over Mondrian’s home, Calder suggested it might be interesting to try and make these objects oscillate, to which the artist replied, "No, it is not necessary, my painting is already very fast.” Mondrian’s response “shocked” Calder, and led him to explore the theories of Neo-Plastic art and develop them into his own artwork. By 1931, Calder was just beginning work on the art that would make him a famous figure in art history: the “mobile,” a term coined by fellow artist Marcel Duchamp to describe Calder’s moving sculptures. By combining the properties of his linear sculptures with the observations of abstraction and movement made in Mondrian’s studio, Calder created abstract sculptures with moveable parts that were subject to the wind or air currents. Using wood and wire, he began to evolve away from using geometric forms in favor of embracing more organic, conceptual imagery. Through the second half of the 1930s, Calder continued to make variations of his mobile model, while working to create new concepts formulated around movement and perception such as moving paintings or the freestanding “stabiles”—a term coined by Jean Arp--that, while remaining fixed, invited the viewer to move around the sculpture in order to gain new perspectives.

During his time in Paris, Calder formed many friendships with other avant-garde artists such as the previously mentioned Jean Arp and Marcel Duchamp. But the most important and influential relationship Calder made was with fellow artist Joan Miro. Throughout the rest of their lives, Calder and Miro remained extremely close friends, and it is in the intimacies of their friendship that some of the most interesting observations of Calder’s work can be made. Between Miro and Calder there developed a “visual dialogue” in which it is clear the painter and the sculptor had extensive influence on each other’s work. Looking at Calder’s stunning mobiles is nearly like imagining the bold lines and colors of Miro’s paintings emerging from the canvas into a three-dimensional sculpture. In fact, the New York Telegram stated in 1936 this exact sentiment, explaining “Calder’s mobiles are like living Miro abstractions." The two artists encouraged experimentation in each other throughout their careers, and it is thanks to Miro that Calder’s work took on innovative evolutions and embraced the surrealism found in much of the former’s portfolio. The natural harmony between the two was so well acknowledged and received by the art world, that in 1961, they were given a joint exhibition in New York, displaying the collections of both side by side.

From the 1940s and into the 1970s, Calder continued to pioneer the Kinetic art movement with his “gongs”, “towers”, “totems” and “animobiles”, showing them at countless exhibitions, galleries, museums, and retrospectives. But it was in that 1972 Calder was offered the unprecedented opportunity to paint a full-sized Douglas DC-8-62 four engined airliner for Braniff International Airways. Excited by the proposition of a “flying canvas”, Calder accepted and after designing several small-scale versions, Braniff chose his “Humor” design to be painted on the airplane. The success of the first collaboration prompted two more requests from Braniff. Calder completed the second airplane—a Boeing 727--in 1975, and was in the middle of working on the third Boeing 727 when he died in November of 1976. The finished craft was dedicated to Calder in a ceremony in 1977.

Alexander Calder's extraordinary work with various mediums and sculptural techniques demonstrate his longtime love of engineering and hand-crafted objects, and today the artist is praised for demolishing the boundaries of sculpture and introducing the world to his brilliantly innovative kinetic art. Having allowed himself to be influenced and shaped by other artists like Miro and Mondrian, Calder’s body of work represents an ever-evolving demonstration of risk-taking, creativity, ingenuity, and extremely impressive technical achievement. Even 40 years after his death, Calder's works like Lily of Force are still fetching over $18 million dollars at auction, and his 1957 mobile Flying Fish just recently fetched over $25 million in 2014, setting an auction record for Calder.