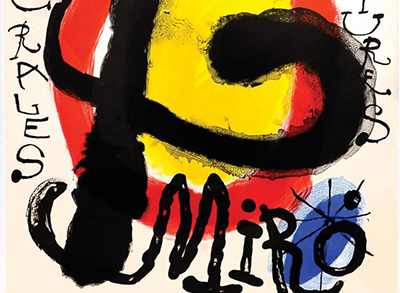

Joan Miró

Joan Miro, born April 20, 1893 in Barcelona Spain, began his artistic career at the age of fourteen, when he enrolled at the School of Industrial and Fine Arts. Upon finishing his classes there, he participated in his first group exhibition of drawings, and six years later catches the attention and encouragement of art dealer Jose Dalmau, who gave Miro his first solo exhibition in 1918. During these early days of his career in Spain, Miro’s work displayed influences of Fauvism, Cubism, and Roman Catholic imagery and themes. In 1920, Miro traveled to Paris where Dalmau strove to get him another solo show, finally succeeding in 1921. Read More

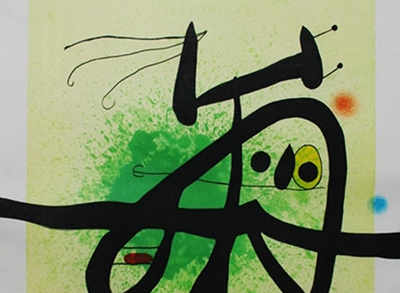

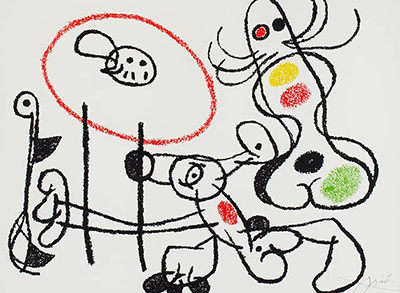

While in Paris, Miro’s personal style and technique began to change as he became involved in the emerging Dada movement, spent time with avant-garde poets, and eventually was exposed to the Surrealist movement in 1924. Under the influence of the other creative types surrounding him, Miro adopted his signature style: organic forms, flattened planes and the sharp, precise use of line. Additionally, Miro’s pride in his Catalan heritage and his inclinations to recreate what was considered “childlike” or primitive art began to emerge and saturate his art. These elements can be seen in his earlier “dream pictures” and "imaginary landscapes”, which broke down figurative forms into abstract, indeterminate concepts, and earned Miro the high praises and respect of the other Surrealists.

It was during this time in Paris that Miro began a close friendship with Alexander Calder, an American sculptor five years Miro’s junior living and working in Europe at the time. The commonalities the two artists shared concerning their influenced yet inarguably unique works bonded Calder and Miro throughout their lives. As their portfolios developed and expanded, a clear complementary relationship became more and more distinguished. Inspired by Calder’s innovative and revolutionary sculptural designs, Miro’s paintings took on a refreshing playfulness, allowing two-dimensional line, form, and color to create a kind of movement achieved in Calder’s moving “mobiles.” The synergy captured and maintained between the two came to define their style of highly inventive art, and as early as 1936, Miro and Calder were often seen as an analogous duo in the art world.

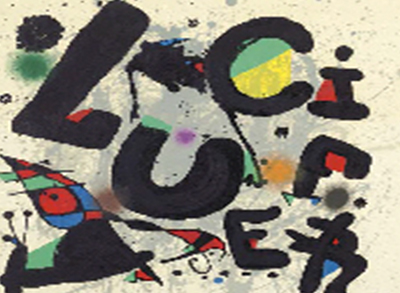

Miro became known for his chameleonic ability to adapt his artistic skill to countless mediums. In this way, he was able to transcend the conventional ways of painting that he considered to be a tool of the bourgeois society utilized to support the upper class culture. Miro famously declared “an assassination of painting” as a means of rejecting the established methods and subject matter of the elitist art world. Throughout his career, Miro explored varied styles of art such as collage, sculpture, engraving, watercolor, pastels, object-paintings, lithography, tapestries, ceramics, and even set and costume design for the ballet. In the years following World War II, Miro became internationally famous and highly sought after. He was commissioned to paint murals for Harvard University and the Terrence Hilton Hotel, and his achievements in ceramics earned him a commission from the UNESCO building in Paris to create for it two enormous ceramic walls.

Miro’s portfolio of work throughout his career suggests an extraordinary breadth of style and technique, from his early still-lifes and landscapes influenced by folk art and Roman Catholicism, to his paintings done in the style of Dutch realism, to his extraordinary work echoing the heart and soul of the Fauvists, Cubists, and certainly the Surrealists. Miro’s signature semi-abstracted geometric and biomorphic forms characterize his desire to dismantle traditional concepts of perception, imagination, and equilibrium in favor of experimentation, playfulness, and simplification. Though never fully subscribing to one particular art movement, Miro instead used the different ideals of each movement as stepping stones along an independent path. This allowed him to create highly unique and unprecedented artworks which continue to inspire artists and delight collectors long after his death on Christmas Day, 1983. In fact, on February 4, 2015, Miro’s painting Women, Moon, Birds (1950) sold at auction for over $23 million dollars, proving the artist’s legacy continues to soar like his stellar imagery and imagination.